Wolfwalkers: An Interview With Directors Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart

I interviewed the film’s two directors. Tomm Moore also helmed Kells (with Nora Twomey) and Song of the Sea. Ross Stewart has art credits on both those films and Laika’s Paranorman. He and Moore wrote the Wolfwalkers story together with Will Collins, who is credited with the screenplay.

AFA: I love the wolf pack in Wolfwalkers. The wolves are often very goofy, but they can also be properly scary, as when they menace a woodcutter and draw blood in the pre-credits opening.

Tomm Moore - The opening came from a note from Nora Twomey [director of Cartoon Saloon’s The Breadwinner]. We had done a lot of work to make the wolves sympathetic, because we felt the first reaction of a modern person to a wolf would be that it’s a scary creature. So we thought about how the wolves would appear to the Wolfwalkers, which would be more like crazy dogs.

[But in the opening] we needed to see the wolves from the villagers’ viewpoint, to be sympathetic towards Robyn and her dad’s point of view. So we set it up that the wolves look a certain way to the woodcutters but that when we met them again with Mehb, we deliberately showed them as a bit goofy and playful. We even drew them slightly differently. Whenever the wolves are under the control of the Wolfwalkers, they don’t have any pupils in their eyes and they’re much more menacing. And then whenever they’re let off the hook, they’re like a big pile of puppies; we drew them less individually and they become like a big mass.

Ross Stewart - We looked at a lot of videos from wolf conservation centres, from various charities that would work with packs of wolves in sanctuaries. You get to see their playful goofy side when they’re playing around the den and they have this lovely endearing family pack. They spend a lot of their time playing and just mucking around. But you would only see that if you were living with them. A human back in the 1600s would never see that; the only interaction they would have with wolves would be when the wolves were attacking livestock or when the people were attacking the wolves, so they would see this vicious side. So it’s only when Robyn goes into the wolves’ den that she sees the more endearing, familial pack side of them.

The wild Wolfwalker girl Mebh reminded me of Aisling in The Secret of Kells, in her attitude and movements. Would you say that Mebh is a more wild and earthy version of Aisling?

The wild Wolfwalker girl Mebh reminded me of Aisling in The Secret of Kells, in her attitude and movements. Would you say that Mebh is a more wild and earthy version of Aisling?

RS- Yes. Aisling’s a bit more supernatural, more mystical, like a fairy creature, and maybe a bit more light, whereas Mebh is definitely of the earth. She’s covered in mud and dirt and a bit rough around the edges. She doesn’t have the same finesse or delicate qualities as Aisling. But there’s the same level of brattiness there, of standing up for herself and not being afraid; not being a bully but being a bit raucous.

Mebh’s dialogue is really funny. Was any of it improvised?

M - We had an interesting process with Mebh. A woman who works with us played the part of Mebh all the time we were storyboarding. And then when we found Eva [Whittaker, who voices Mehb in the film], they worked together to prepare her. But Eva just owned the character and went off in her own direction. She really did bring so much to it, even just little things like intonation and giggling at the right places. It made the character seem real and not forced.

S- I don’t think there was too much dialogue rewriting but the acting brought so much to the delivery. If we had allowed the dialogue to go off script, Mebh might have ended up sounding too cultured and not of the forest. We had to take care that she seems a genuine child who lived with wolves.

Compared to your previous films, Wolfwalkers feels more like an action-adventure story.

Compared to your previous films, Wolfwalkers feels more like an action-adventure story.

M – Yes, it was a conscious choice right from the beginning as we were writing it. We felt that it had stakes and drama built into it. If you were making a comparison, Song of the Sea was referring a bit more to Totoro or Spirited Away in terms of tone. Wolfwalkers is definitely on the side of [Princess] Mononoke.

S - A lot of the action sequences were storyboarded by a guy called Iker Maidagan, who’d worked at Blue Sky. One of his favourite films is Indiana Jones, so he storyboarded a lot of three-dimensional perspective shots, a lot of intense camera angles; even that was a bit of a shift away from our other films. We didn’t really know how we were going to pull it off, but we thought if we were going for an action movie then we should go for the action storyboarding too, and figure out how to do it later.

M - We had a fantastic team of storyboarders and we “cast” the boards to different people depending on their strengths. What was amazing was how many of the storyboarders at this stage are actually directors in their own right. Guillaume Lorin [who recently directed a French TV special, Vanille] and Louise Bagnall [director of the Oscar-nominated short Late Afternoon], they brought their sensibilities to it. It was a very collaborative process compared to the previous storyboards.

We had editing help from a guy called Darren T. Holmes in the States [film editor on The Iron Giant and How To Train Your Dragon]. He brought a certain pace to the editing in those sequences.

We had editing help from a guy called Darren T. Holmes in the States [film editor on The Iron Giant and How To Train Your Dragon]. He brought a certain pace to the editing in those sequences.

M - We were worried and it never came up. I think we played it pretty gently. It’s off-screen and it has a bit of a fun ‘80s action movie feel, where the soldiers get whipped up into the trees and so on.

S – It’s funny, though. When you look at, at say, Indiana Jones, they do get shot…

M - Shot dead!

S - But they die in these comical ways…

Both - AARGH!

S - ...And you never really think, Oh that person’s dead, a family’s grieving, it’s just a throwaway… (laughs).

M - The only thing there was a little bit of worry about, because Apple is very forward thinking, were the guns, because they thought that maybe kids might see guns as cool. But once they understood the guns were only handled by the bad guys, and that these were historical muskets, not something that a kid could find now, they were okay with it.

M - The only thing there was a little bit of worry about, because Apple is very forward thinking, were the guns, because they thought that maybe kids might see guns as cool. But once they understood the guns were only handled by the bad guys, and that these were historical muskets, not something that a kid could find now, they were okay with it.

I confess that, as someone taught history in England, I never learned about Cromwell’s terrible oppression of Ireland, or how much he is hated there.

M - Yeah, he’s our Hitler (laughs). It’s a curse, isn’t it? - People put the curse of Cromwell on you and stuff.

S - He’s our cultural bad guy. When we were researching what he had done, we found he was pretty much a bad guy in the north of England and Scotland as well. He followed a campaign of ruthless domination of the local people as he moved up to the north of England and Scotland and then down into Ireland.

The term for Ireland at the time was “Wolf Land” and it used to be considered a totally wild, uncivilised, savage country that needed to be tamed. So it was very much the mindset of the people at the time that if you lived this wild life, you were a savage. It was their duty to bring civilisation to the country. Unfortunately, part of that civilising meant the deaths of an awful lot of people, and the deaths of the wolf population too.

And yet you present Cromwell as a man of (cruel) integrity; he clearly believes he’s the hero.

M – That’s what we really wanted. We wanted to avoid the moustache-twirling villain who enjoys being bad. When we watched a Cromwell movie from the 70s [probably Ken Hughes’ Cromwell, starring Richard Harris], we could see that, in some people’s eyes and certainly in his own, he was kind of a Braveheart figure. He overthrew a king who he felt was corrupt, and he tried to bring democracy of a kind. So we tried to bring a little bit of nuance, that he was a genuine believer in his world view. Which is probably the most dangerous kind of person, utterly convinced by their beliefs and ideology that they’re good.

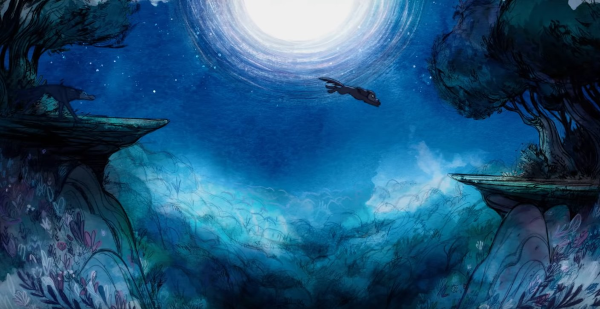

The central sequence, in which Robyn runs joyously through the forest in wolf form, is terrific. Can you talk about how it developed?

M – That’s what we really wanted. We wanted to avoid the moustache-twirling villain who enjoys being bad. When we watched a Cromwell movie from the 70s [probably Ken Hughes’ Cromwell, starring Richard Harris], we could see that, in some people’s eyes and certainly in his own, he was kind of a Braveheart figure. He overthrew a king who he felt was corrupt, and he tried to bring democracy of a kind. So we tried to bring a little bit of nuance, that he was a genuine believer in his world view. Which is probably the most dangerous kind of person, utterly convinced by their beliefs and ideology that they’re good.

The central sequence, in which Robyn runs joyously through the forest in wolf form, is terrific. Can you talk about how it developed?

S - In script form, we just had a little tiny paragraph saying Robyn runs around with Mehb and the wolves exploring what it’s like to be a wolf, and that was it. We just knew that it would be expanded visually with the board artists. But really, it had to be the point where Robyn’s worldview is changed utterly by what she experiences. She can never go back to living the life that she used to live after experiencing something like this. It has to be a completely new world opening up to her.

So Guillaume Lorin, the storyboard artist, was given the first task of exploring this little sequence. He brought in this beautiful mindfulness aspect, where it’s really just about Robyn exploring the sensations of being a wolf, whether it’s letting the rain just fall on her face and hearing the thunder, those kind of shots. I think it does serve as an emotional tentpole, and I think that’s why it works so well with just the song going over it. Instead of a boring montage, it becomes a high point, a glorious audio-visual climax, Robyn’s sensation of being a wolf.

It does become the climax of the second act, but it happened quite organically like that. And Tomn found the song kind of organically too, almost by accident, on his playlist one day. [The sequence is accompanied by a version of the song Running With The Wolves by the Norwegian singer-songwriter Aurora, released in 2016.]

T - Yeah, before that we hadn’t talked about the sequence having such a catchy tune. We talked about it being a kind of mindful moment and we probably expected Kila and Bruno to come up with an orchestral backdrop. [The Irish group Kila and the French musician Bruno Coulais created most of the music on Wolfwalkers, following their earlier collaborations on Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea.]

So people were a little bit dubious when we tried out the song. I said, “Let's just try it and let’s see how it goes,” and then it grew on everyone. [The original song is available here.] And then we adapted it with the orchestra, with Kila and Aurora re-recorded it with slightly different words, and it became part of the movie.

S - The original Aurora song was quite electronic. I think a lot of people’s first reactions to hearing it were like, this is really out of style for the rest of the film; you can’t have a film set in 1650 with a modern pop song with electronic beats! We were a bit cautious about how it would be recorded, but we knew that Bruno and Kila and Aurora would do justice to the film.

There’s also a lovely little scene where Robyn is ‘acting out’ the conversation she’s going to have with her dad about how to solve the wolf problem. How did that come about?

S - The original Aurora song was quite electronic. I think a lot of people’s first reactions to hearing it were like, this is really out of style for the rest of the film; you can’t have a film set in 1650 with a modern pop song with electronic beats! We were a bit cautious about how it would be recorded, but we knew that Bruno and Kila and Aurora would do justice to the film.

There’s also a lovely little scene where Robyn is ‘acting out’ the conversation she’s going to have with her dad about how to solve the wolf problem. How did that come about?

M - We were rewriting the beginning of the movie to make sure that the focus was very much on Robyn. That was an exposition-y bit that was hard for us. I remember Louise Bagnall, another director in the studio who worked on Wolfwalkers as a storyboarder, came up with that moment: “What if I told you I could get rid of the wolves…?” It became known as the “What if I told you?” sequence.

And we realised we had something really fun, because we had a chance for the young Robyn actor, Honor Kneafsey, to do an impersonation of Sean Bean. We didn’t know if it was going to work until they were literally playing the parts. Sean would read the line and then Honor would do her best impression of him. It was really fun to record and we knew we had something, because just the voice was fun. And then the animators took it to another level, with loads of cute little ideas; like Robyn’s hair coming forward to look a bit like Sean's sideburns, and her talking to his hat, loads of fun stuff.

The very first time we see Robyn, for a few seconds we see her in an intense woodcut style.

S - It’s how she sees herself. It’s like going into Robyn’s imagination. She’s playing at being the hunter, so in her head she’s really scary and intimidating.

Wolfwalkers also has cartoon moments that play with ideas of constraint and release; for instance, when the wolves are straining eagerly against a magic barrier, or where a flock of sheep spring out of a cage in one big woolly block.

M - Yes, it speaks to the theme but it’s also just fun, and we had some animators who are more cartoony animators normally. That’s where they could excel.

S - We knew that we had to inject humour wherever we could because it was in danger of turning into a really dark film. The fact that it’s set in 1650 with a brutal oppressor; there are so many dark elements in it. We knew we should try and lighten the tone a bit, with Mehb and the wolves, wherever we could, just so it’s not such a depressing movie! (laughs)

You’ve cited a range of films as influences. Did you watch the Japanese film The Wolf Children, directed by Mamoru Hosoda, which also features children who can take wolf form?

You’ve cited a range of films as influences. Did you watch the Japanese film The Wolf Children, directed by Mamoru Hosoda, which also features children who can take wolf form?

M - Yeah, I watched it early on and I was relieved that what Hosoda was doing was quite different from what we were doing. We’re actually going to speak to Hosoda next week because he’s interviewing us for the Tokyo Anime Awards. I’m excited to speak to him and his daughter is going to play one of the girls in the Japanese version, which is kind of amazing. The Wolf Children is a gorgeous movie; I felt that it was very nuanced. It has a much more modern setting but it deals with some of the same themes, about wildness and trying and trying to fit in as a wolf.

S - If we had written Wolfwalkers set in contemporary Ireland, it would have been a very different film. Setting the film in 1650, it immediately takes on a fairy tale feel, almost like a story you might read in a compendium of old fairy tales or something like that.

M - I think it’s what made it most different from The Wolf Children.

Some of the scenes with Cromwell’s soldiers reminded me of Richard Williams’ The Thief and the Cobbler; was that deliberate?

S- I think what you’re referring to is the movement of the soldiers, kind of clockwork.

M - Like the War Machine [a celebrated sequence in The Thief and the Cobbler].

S- It also helps serve that story. If you lead a life of orders, following them ruthlessly and without question, that’s when you end up like a robot.

M - I think Thief and the Cobbler got into the DNA of the studio. We were so inspired by Williams early, early on when we were in college and we found a VHS tape of the movie before it got out into the popular consciousness with the internet. I remember feeling like we’d discovered this lost treasure of animation which no-one had ever seen. It felt like we were on the inside. It was something that we looked at a lot during the development of Secret of Kells, just as an influence.

What was so mind-blowing was that I discovered it about ‘95, ‘96, when the whole industry was veering towards realism, they were all so impressed by Toy Story. And to see somebody 25 years earlier had been pushing the boundaries of what hand-drawn, 2D animation could do, inspired by Persian miniatures and stuff. So for us it’s always there in the background.

The film has a couple of big ‘gasp’ moments, both involving characters who we’re invested in being shot by arrows.

S - I think the bird getting shot [early in the film] establishes that in this world, you can get hurt, it’s not a safe story, there are consequences.

M - The feeling when (a certain character) gets shot was supposed to be a shock. We tried to build the story with a sense that the movie could end there, with the characters reunited, Robyn’s dad Bill trapped in the town with his belief system, and they’re all going to leave and it’s all going to be okay. The fact that (a particular character) shoots is a second shock. You think the movie’s almost over, and then it ramps up again to another level.

Regarding what happens to Cromwell at the end of the film, did you have any compunction about changing history?

M – Yeah, we did and that’s why we didn't call him Oliver Cromwell in the body of the movie. We called him Lord Protector because we felt that outside of these islands, most people would just recognise him as a military type character. I think it was Nora who said that we should be careful on the Inglourious Basterds side of things. You don’t draw people out of the story and lose the emotion because they’re like, “Wait, what?” But it’s a complete fantasy other-Ireland of 1650, with real magic and wolves who talk to each other, so we felt we could do that. But we talked about it. We even storyboarded other endings where he survived.

S - But it is an ambiguous ending for him. He’s gone from the story, but he could easily survive. And also, it’s even an ambiguous end for the wolves, in that the wolves go off into the sunset but in truth within a hundred years, all wolves were extinct in Ireland. It’s just a snapshot of a brief moment in time. But it’s fun to play around with history!

ANDREW OSMOND IS A BRITISH JOURNALIST SPECIALISING IN ANIMATION AND IS THE UK EDITOR OF ANIME NEWS NETWORK. HIS BOOKS INCLUDE BFI CLASSICS: SPIRITED AWAY, 100 ANIMATED FEATURE FILMS AND SATOSHI KON: THE ILLUSIONIST. HIS WEBSITE IS ANIME-ETC.NET

WOLFWALKERS opens in cinemas nationwide in the UK & Ireland from October 30 from Wildcard Distribution [With Previews on Monday October 26] and on November 13 in the United States from GKIDS Films, and will be available on Apple TV+ From December 11.